I have a face that does not frown and hands that do wave. I do not walk but move around. I’ve met at least eight presidents. What am I?

Vogue Editor Anna Wintour Is Now Dame Anna

June 27, 2017Fashion Review: Dior Homme Stays in Its Safe Space

June 28, 2017I have a face that does not frown and hands that do wave. I do not walk but move around. I’ve met at least eight presidents. What am I?

- Americana Grandfather Clocks

- Antique Grandfather Clock

- antique grandfather clocks

- Architectural Clocks

- Clock

- Clocks

- Floor Clock

- floor clocks

- Grandfather Clock

- Grandfather Clocks

- Grandfather Clocks History

- grandfatherclock

- grandfatherclocks

- History of Grandfather Clock

- Howard Miller Presidential Grandfather Clocks

- Interior Decorating

- Interior Design

- Long Case Clocks

- longcase clocks

- News Clocks

- Tall Case Clocks

- tallcase clocks

- Timepieces

- Uncategorized

A grandfather clock — well, the grandfather clock in the Oval Office, that is.

As told in a recent Boston Globe article, the grandfather clock in the Oval Office featured recently in the Oval Office meeting between President Donald Trump and then FBI Director James Comey. Director Comey frequently described the goings of key aides Jared Kushner and White House Chief of Staff Reince Priebus during US Senate Intelligence Committee Hearings as leaving by the door next to the grandfather clock.

Is this grandfather clock perhaps one of if not the most famous of grandfather clocks through history, and imagine the stories it could tell if the grandfather clock could talk.

Aimee Ortiz’ article in The Boston Globe (link above) gives a great summary of the maker and the history of this grandfather clock and other artifacts over the years, many of which made it to the hallowed halls of The White House and other key Government Buildings.

Acquired in 1972, the old clock was made by John and Thomas Seymour of Boston, circa 1795-1805, and has stood in the Oval Office since 1975, according to the White House Historical Association.

Papers housed at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library and Museum in Michigan offer a little more light on the origins of the clock.

According to a memo regarding “materials for the Queens’ Bedroom” that was prepared for First Lady Betty Ford in 1975, former First Lady Patricia Nixon was partially gifted (and partially purchased) the “wonderful collection of very beautiful and rather feminine American furniture” by the Seymours from Boston’s Vernon Stoneman in 1972. The Ford memo lists the father-and-son duo as being from Salem.

The Peabody Essex Museum, however, states that the Seymours landed in Boston in 1793.

Having hosted an exhibition on Seymour furniture from November 2003 to February 2004, the PEM explains that the Seymours benefited from Boston’s changing social landscape at the time.

“New leisure activities, and growing wealth led to the construction of larger houses and created demand for higher quality furniture and new forms, such as sewing tables, ladies’ desks, sideboards, and lap desks,” the PEM writes. The “increased prosperity and foreign trade” as well as a “consistent supply of the exotic and rare woods and veneers” led to the Seymours’ prevalent style of using mahogany and rosewood, according to the PEM.

Stoneman, the Boston lawyer who wrote what’s considered to be THE reference book on the Seymours and collected the furniture that was eventually sent to Washington, worked with White House curator Clement Conger on the deal that included a tax-deductible gift of a “pedimented tambour desk” as well as a mirror.

In 1973, Conger called the transaction with Stoneman the “coup of the 20th Century.” In all, 30 pieces, worth “somewhere between $250,000 and $500,000,” were sent to the White House.

In 1976, Stoneman told the Globe that the tambour desk “is the piece Mrs. Ford is said to touch every time she comes down the stairs.”

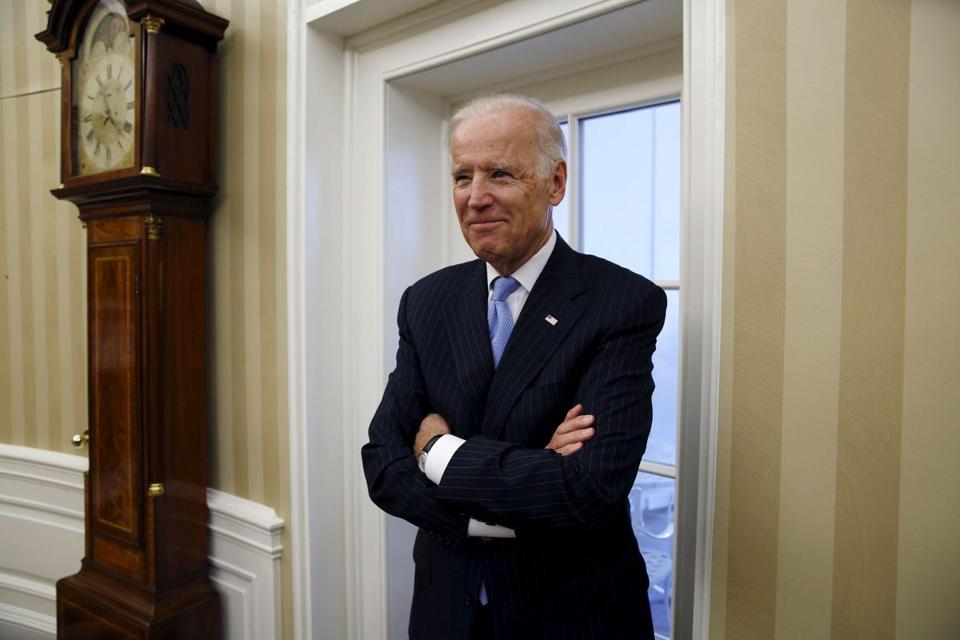

Grandfather Clocks in Oval Office adjacent to former Vice President Joe Biden